Paper Submitted by McKay Cunningham

Professor and Director of Experiential Learning

College of Idaho

Historical Background

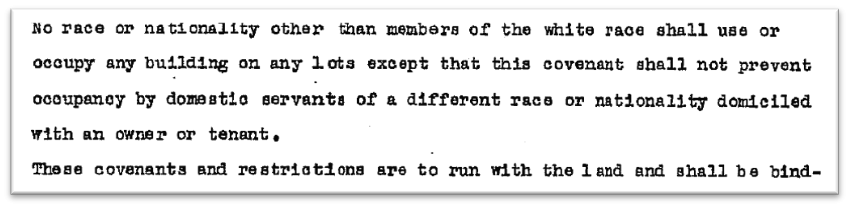

During the twentieth century, both redlining and racial covenants were widely used tools to ensure housing disparities based on race. Developers and private land owners embedded racial covenants in property deeds, prohibiting all non-whites from owning, renting, or occupying property – unless doing so as a domestic servant.

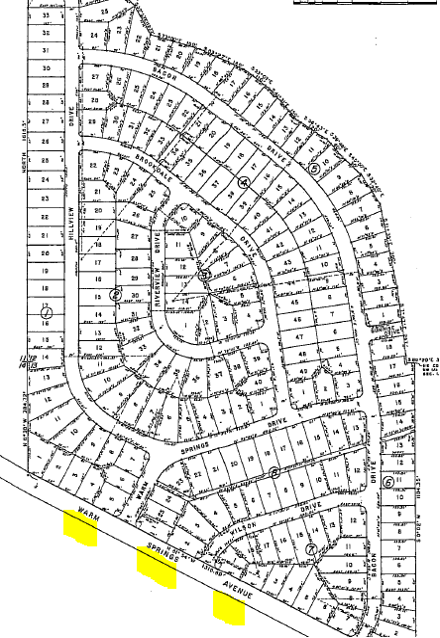

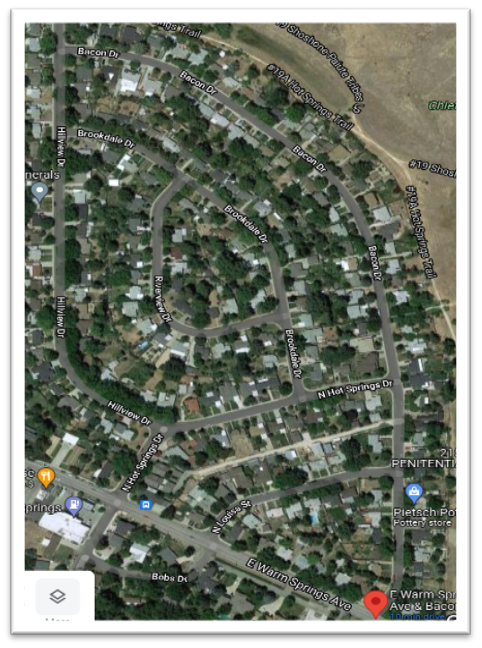

Typically, these racial covenants “ran with the land,” a legal term that signifies perpetuity. In other words, the racial covenant was not tied to the original owner of the land. It continued to bind successive owners because it “ran with the land.” The Warm Springs Park subdivision in Boise, for example, includes the covenant above and is tied to all the homes within the subdivision as shown below.

2021

There are likely thousands of properties in Ada County alone that still have racial covenants in their titles. A research team at the College of Idaho is working to identify all racial covenants in Idaho and provide that information to the public. Although the research has just begun, the team has unearthed over 50 subdivisions in Ada County alone with racial covenants.

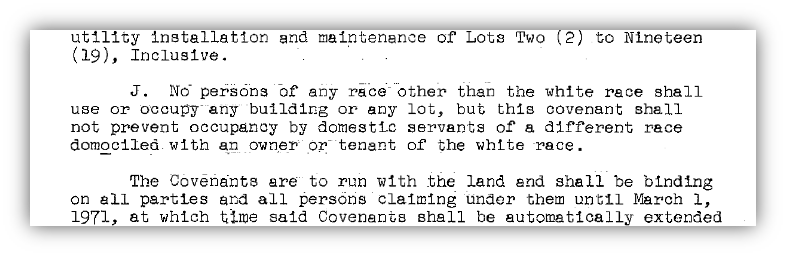

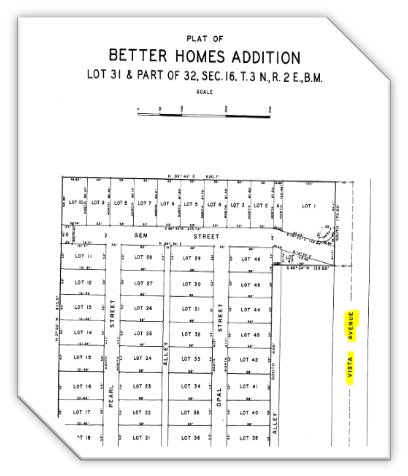

Nationwide, it is estimated that more than half of all residential properties built during the post-war housing boom included racial covenants.[1] Here is another example of a subdivision on Vista Avenue in Boise.

2021

Redlining

Racial covenants often worked in conjunction with redlining. Redlining was a federal policy that provided federal financial backing for homeownership in some neighborhoods, but not others. The federal government often created colored maps indicating which areas should receive financial backing to spur homeownership and which areas should not. The red areas in these maps were deemed “hazardous” because people of color lived in those areas.

Redlining had its heyday in the decades following World War Two—a golden era of the American economy. The ability of working-class families to attain middle-class wealth was spurred by federal government programs, like the provision of mortgages with little or no down payment. With the federal government’s backing, homes were affordable, even for African-American and Latinx working class families. But the government refused to back their loans. As housing values shot up during this period, the home equity that white homeowners realized assured them intergenerational wealth—an opportunity denied to communities of color.

Contemporary Consequences

Although redlining was outlawed in 1968 with the enactment of the Fair Housing Act, it remains highly relevant today. Similarly, the Supreme Court ruled racial covenants unenforceable in 1948, but the historical impact continues to affect communities of color.

Idahoans are often dismayed to find their homes burdened by racial covenants. Many are unaware that racial covenants are unenforceable and believe that they cannot live in certain neighborhoods if they are not white. Others know the covenants are unenforceable but feel unwelcome moving to or living in neighborhoods that maintain these racial restrictions in their titles.

Most pointedly, the connection between homeownership and wealth accumulation is critical. It is one of the few ways that any household, but particularly low or middle-income households, can accumulate wealth and pass that wealth to future generations. Today, the wealth gap that separates whites from communities of color reflects the continuing impact of these historical practices. The net worth of a typical white family, $188,200, is nearly eight times greater than that of a black family at $24,100 and more than five times the wealth of a Latinx family at $36,100.[2]

Moreover, without access to government backed mortgages, people of color, as well as whites who lived among and near people of color, remained relegated to the rental market. Black, Latinx, and poor white households, for example, are predominately renters rather than homeowners. The Survey of Consumer Finances shows that the average homeowner has household wealth of $255,000, while the average renter has household wealth of $6,300.[3]

Racial Covenant Legislation

This Legislation does not attempt to fully remediate these historic disparities. Instead, it allows an owner or tenant of property that is subject to a racial covenant to record a modification document that specifically voids the racial covenant. In other words, it provides property owners with a simple mechanism to nullify racial covenants in their respective deeds.

The modification document would be part of the deed or chain of title to the property and would state that the discriminatory language of the racial covenant is void and unenforceable. The Legislation is not a government mandate to remove all such covenants. Rather, the Legislation allows Idahoans to choose whether to file modification documents to their deeds. The estimated costs to implement this Legislation is zero.

[1] Nancy H. Welsh, Racially Restrictive Covenants in the United States: A Call to Action, available https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/143831/A_12%20Racially%20Restrictive%20Covenants%20in%20the%20US.pdf.

[2] Neil Bhutta et al., Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, FEDS Notes (Sept. 28, 2020), https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.htm.

[3] Fed. Res. Sys., 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm (last updated May 20, 2021).